Plants didn’t wait for us to admire their leaves. Over hundreds of millions of years they evolved into chemical factories producing a staggering variety of compounds that go far beyond the basics of growth. In this article we’ll explore how evolution shaped plants into “natural chemists”, why this matters in terms of their survival and interaction, and what it means for anyone working with plant chemistry today.

1. A quick evolutionary snapshot of land-plants

The story begins in water. The ancestors of today’s land plants were green algae, which gradually adapted to terrestrial life. Key innovations occurred: roots, leaves, vascular tissue, seeds, or flowers. Many of these changes required adaptations not just in form, but in chemical structures exposed to new stresses, new herbivores, new competition.This evolutionary backdrop set the stage for plants not only to live and grow, but to defend and interact chemically.

2. Why did plants shift into specialised chemistry?

Sessile lifestyle demands more than size

Unlike animals, plants cannot move when conditions change. They must stay rooted and adapt. One way is by evolving chemical tools for defense, attraction, signalling. This is chemical strategy in place of movement.

Herbivores, pathogens, and competition

As plants moved onto land and diversified, herbivores and pathogens evolved in parallel. Plants responded by evolving chemical defenses: secondary metabolites that deter feeding, inhibit microbes, reduce competition.

Environmental challenges

Land life brought UV radiation, drought, nutrient fluctuations. To cope, plants developed chemistry to shield themselves, e.g., UV-absorbing flavonoids, root exudates that affect neighbouring plants or microbes. Together, these pressures pushed plants toward greater and greater chemical complexity.

3. The march from basic metabolism to chemical diversity

Primary to specialised

Plants start with primary metabolism (growth, reproduction) and then branch into specialised (secondary) metabolism of the chemicals for interactions.

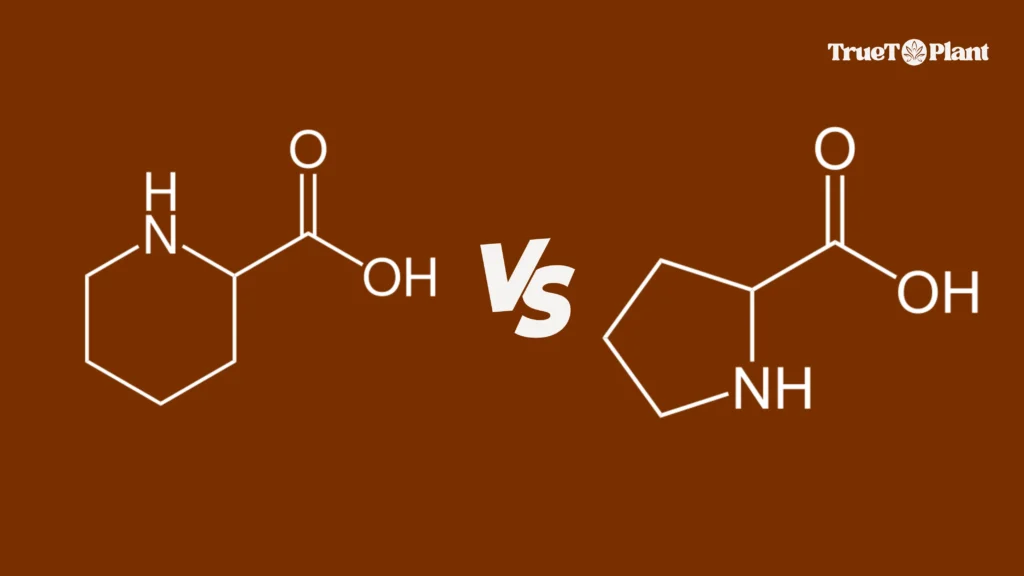

Gene duplication, enzyme innovation, pathway branching

Evolution equipped plants with new enzymes, duplicated genes, and pathway ‘side-arms’ that lead into secondary metabolites. For example, once a particular enzyme emerged that produced a deterrent compound, it gave a selective advantage. Research shows “secondary plant metabolites… evolved in relation to environmental conditions.”

Co-evolutionary arms-race

Plants evolve chemical defenses; herbivores evolve detoxification or avoidance mechanisms; plants evolve new defenses. This arms-race generates rich chemical diversity.

Lineage-specific chemistry

Many secondary metabolites are restricted to certain plant lineages or species showing that chemical innovation is tied to evolutionary history.

4. Key evolutionary milestones in plant chemistry

The move to land and novel chemistry

When plants moved from water to land, they encountered novel stresses (UV, desiccation, herbivory) and developed chemical adaptations (UV-protectant compounds, tougher tissues, deterrents) early on.

Seed plants, flowering plants and chemical explosion

With the emergence of seeds and ultimately flowers, plants entered new ecological interactions (pollinators, seed dispersers, herbivores). These interactions drove the evolution of new chemicals for attraction (scents, colors) and defense.

Recent examples of chemical novelty

Studies show that even within a genus, some species evolve novel defense compounds distinct from their relatives e.g., in the genus Erysimum some species produce both ancestral glucosinolates and new cardenolide compounds.This highlights that plant chemical evolution is ongoing, not ancient, and not finished.

5. Why this evolutionary view matters for plant chemistry

Understanding source of diversity

If you appreciate that the chemical profile of a plant is the result of millions of years of evolution, you begin to see why some plants produce unique compounds while others don’t.

Predicting and discovering new compounds

Knowledge of evolutionary lineage helps researchers find plants likely to produce new chemicals (e.g., understudied families, plants in extreme habitats).

Applied fields: agriculture, medicine, ecology

- In agriculture: Knowing how plants evolved chemical defenses helps in breeding or engineering resistance.

- In medicine/phytochemistry: Many drugs trace back to secondary metabolites evolved for defense.

- In ecology: The evolutionary chemical arsenal of a plant informs how it interacts with herbivores, microbes, competitors.

Variation across plants explained

Different species or populations of the same species have different chemical profiles because evolution shaped them differently according to environment, herbivory pressure, resource availability.

6. A walk-through: evolution of a chemical defense

Let’s imagine a simple scenario to bring it alive:

- A plant grows in a new habitat where herbivore pressure increases.

- Random mutation leads to production of a compound (say a small alkaloid) that deters herbivores.

- That plant variant has advantage; the gene for the enzyme producing the compound spreads.

- Over time gene duplication allows modified enzyme to produce a variant compound with improved effect.

- Meanwhile herbivores adapt, so plant evolves new compound. This cycle repeats (“arms-race”).

- The resulting lineage has a suite of unique chemical defenses (specialised metabolites) that define it.

This is essentially how plants became “natural chemists” through evolution, selection, adaptation, diversification.

7. The chemical results: terpenes, alkaloids, flavonoids and beyond

What plants produced through this evolutionary process are the major classes of secondary metabolites:

- Terpenes/terpenoids: large, diverse class, many roles in defense, signalling.

- Alkaloids: nitrogen-containing, often potent, evolved for defense, signalling.

- Flavonoids/phenolics: UV-protection, pigmentation (pleiotropic roles), defense.

Each of these chemical classes is shaped by evolutionary pressures and trades off growth vs defense, resource allocation vs interaction.

8. Implications for plant chemistry in practice

Variability & provenance matter

Because evolution has shaped chemical profiles, the origin of a plant (its environment, lineage) matters. Two plants of the same species from different habitats may differ chemically.

Targeting neglected lineages

Evolutionary insight helps identify plants for novel chemistry. Families with few studied compounds may hold “evolutionary chemical novelty”.

Engineering & synthetic biology

Understanding evolutionary enzyme pathways means we can replicate or modify them for production of valuable metabolites.

Conservation & biodiversity

Loss of plant species means loss of unique chemical lineages. From an evolutionary-chemistry standpoint, that’s a loss of natural chemical libraries built over millions of years.

9. Final thoughts

Plants did not become chemical factories overnight. Through a long evolutionary journey adapting to land, to herbivores, to competition, to environment they built complex, specialised chemistry. The next time you smell a plant, admire its color, or read about a botanical extract, remember: you’re witnessing the legacy of natural chemistry shaped by evolution.

Recognising this evolutionary dimension adds depth to understanding plant chemistry, gives context to diversity of secondary metabolites, and highlights why plants remain so fascinating (and so useful) in science, agriculture and medicine.