Plants do far more than photosynthesise and grow. They are chemical producers, reacting to light, soil nutrients, and stress by altering the mix of secondary metabolites they generate. These adjustments influence flavor, color, defense, medicinal value and ecological interaction. In this blog we will explore how light, soil and stress shape a plant’s chemical profile and why this matters for anyone working with plant chemistry.

1. Why environment matters for plant chemistry

Plants are rooted in one place, so their only option for responding to changes in environment (light intensity, nutrient availability, stress from herbivores or drought) is through adaptation, often via changes to their chemistry. As described in an article on Secondary metabolism: “Secondary metabolites… are produced by many microbes, plants, fungi … where chemical defense represents a better option than physical escape.”

The pathways that generate these compounds are sensitive to environmental inputs and thus the same species of plant grown under different conditions can produce quite different chemical profiles. This is critical when you’re interpreting plant chemistry or designing botanicals, extracts, or even ecological experiments.

2. Light: the first shaping influence

The role of light beyond photosynthesis

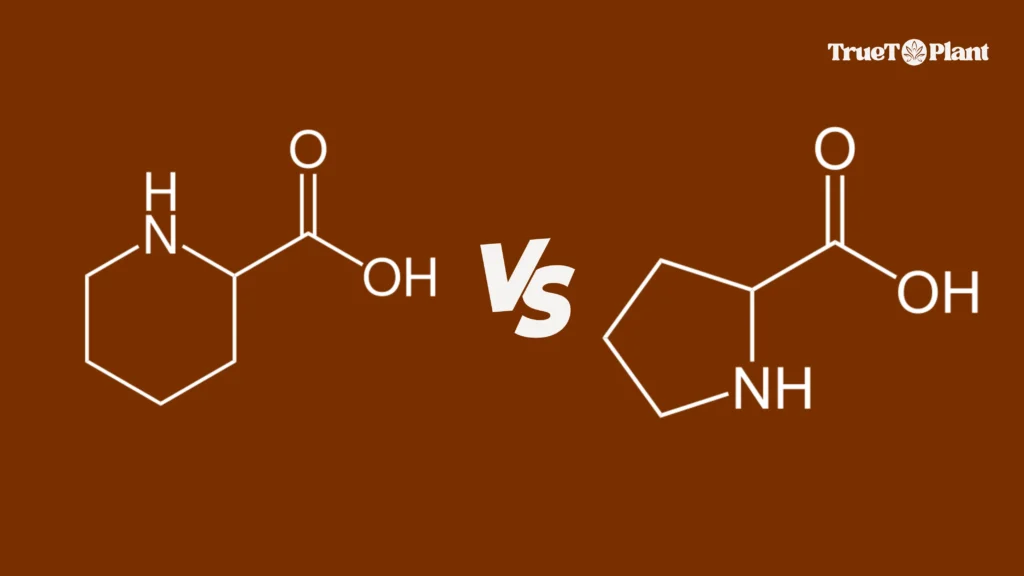

Light drives photosynthesis, of course, but it also influences metabolic pathways that lead into secondary metabolite production. For example, many flavonoids have a role in UV-protection. Excess light (especially UV) acts as a stressor. Plants respond by producing protective compounds (e.g., phenolics and flavonoids) which can absorb or dissipate excess radiation.

How varying light intensity affects chemistry

Recent research indicates that light intensity is a key factor for biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. Higher light intensity often correlates with increased accumulation of certain secondary metabolites, especially those involved in defense and UV protection. At the same time, plants under low light may shift metabolism to preserve resources and down-regulate less essential pathways.

Adaptive behaviours

Plants may also physically adapt their leaf orientation or internal structures. For example, the phenomenon of Paraheliotropism (leaf movement to reduce light interception) helps plants avoid photodamage in high-light environments. These physical responses mean that the chemical responses to light are intertwined with structural and physiological changes.

3. Soil nutrients and the root environment

Nutrient availability and primary metabolism

The soil supplies essential nutrients for plant growth. These primary nutrients (C, H, O, N, P, K, etc.) are critical for growth, reproduction and basic metabolism. If nutrient supply is limited, plants may redirect resources away from growth towards other processes including stress responses and secondary metabolite production.

How soil influences secondary metabolism

While direct data may be sparser, the rhizosphere (the root-soil interface) is a hub of chemical interactions. Plants exude compounds into soil that influence microbes and nutrient cycling. These root exudates often include secondary metabolites or related compounds. When the soil is nutrient poor or imbalanced, the plant’s chemical investment may shift: for instance towards allelopathic chemicals (see Allelopathy) that suppress competitor roots.

In short: soil nutrient status affects not only growth but also chemical strategy.

Soil stress and chemistry

In soils with nutrient deficiency, toxicity (e.g., heavy metals), poor structure or drought, plants often experience stress at the root level. That stress can signal production of defense or adaptive secondary metabolites, for example antioxidants or root exudates, that change microbial communities. While this area is rich for research, early evidence shows soil stress is an important driver of chemical change.

4. Biotic and abiotic stress: the chemical trigger

What is abiotic stress?

Abiotic stress refers to non-living environmental factors that negatively affect plants, such as drought, extreme temperatures, high light, UV, nutrient deficiency, and salinity.

These conditions create metabolic challenges (e.g., oxidative stress, impaired photosynthesis) which often lead to changes in secondary metabolite profiles as plants attempt to cope.

What is biotic stress?

Biotic stress involves living assaults: herbivores, pathogens, competing plants. As noted in the article on Plant defense against herbivory, many plants produce secondary metabolites (allelochemicals) that influence herbivore behaviour, growth or survival. Thus, when a plant is under attack it may shift chemical production significantly.

How stress translates into chemical change

- Stress signals (wounding, herbivore damage, UV exposure) activate signalling pathways in the plant which up-regulate enzymes tied to secondary metabolite biosynthesis.

- For example, phenylpropanoid pathway enzymes may be induced under UV or pathogen attack.

- Some studies (e.g., recent reviews) show that stress combinations (light + drought + high temperature) can have synergistic effects on metabolite levels.

So in effect, stress acts as a signal that causes chemical adaptation.

5. Putting it together: how light, soil and stress combine in real plants

Case scenario: High light + nutrient-poor soil

A plant grown in intense sunlight on a poor soil (low nitrogen, phosphorus) will:

- Have high light energy input → may produce more UV-protective flavonoids and phenolics

- Have limited nutrients → growth may slow, resources diverted into defense/maintenance rather than biomass

- Experience potential oxidative stress → antioxidants and secondary metabolites may increase

Case scenario: Shady site + rich soil

A plant in low light but rich soil may:

- Prioritize growth (using high nutrients) rather than defense

- Have less need for UV‐protective compounds, so secondary metabolite levels may be lower or different

- Possibly engage in different root chemistry (exudates) to maximise nutrient uptake

Soil + root stress combined with above-ground stress

For example, drought (abiotic) + root nematode attack (biotic) + high light (abiotic) = complex signalling → the plant may produce an array of defense-style metabolites both above and below ground, shift allocation from primary growth to survival strategies, change root exudation profiles, alter microbial symbionts in rhizosphere. The combined effect often results in more varied or higher levels of secondary metabolites.

6. Why these effects matter for practitioners

If you’re working in botany, plant extracts, agriculture, medicinal plant production or ecological study, understanding these environmental influences is key.

- Crop & herb quality: The chemical profile of an herb or medicinal plant may depend on how much light it had, what soil nutrients were available, and whether it was stressed. Two plants of the same species can have very different chemistry.

- Standardization challenges: If you’re extracting compounds for product development, you’ll need to control or to at least closely monitor environmental variables (light, soil nutrients, stress levels).

- Ecological interpretation: When interpreting metabolomics data or plant chemistry in the field, you need to consider context: high secondary metabolites → possibly stress, nutrient limitation, or other pressure.

- Breeding/selection: If you are selecting plants for high production of certain metabolites, knowing how light and soil affect expression helps you design trials or production conditions.

7. Practical tips for optimising chemical outcomes

Here are some actionable pointers:

- Monitor light levels: Ensure you know whether plants are in full sun, partial shade or shade. The UV component matters for many protective metabolites.

- Check soil nutrient status: Analyzing N, P, K, micronutrients helps you understand whether plants are nutrient-limited and thus may shift chemistry.

- Consider stress treatments: For producing higher levels of certain secondary metabolites you might intentionally apply mild stress (e.g., moderate drought, light stress) under controlled conditions.

- Document environmental history: For example, consistent soil conditions, light cycles, temperature variation. This helps correlate chemical results with environmental factors.

- Use metabolite profiling over time: Track how chemical levels change as plants undergo stress or changes in light/soil. This gives you a dynamic understanding of chemical expression rather than a static snapshot.

8. Summary

Environmental factors, light, soil nutrients, and stress, play a central role in shaping a plant’s chemical expression. Secondary metabolites are not static; they respond to signals from the environment and help the plant adapt. For anyone working with plant chemistry, botanical extracts, or ecological studies, acknowledging these influences is crucial for interpreting results, optimizing production, and ensuring consistency. The chemical profile of a plant is its story of growth, environment, stress and defense and by reading it we gain insight into both plant and the world around it.