Somewhere between nature photography and climate storytelling, the phrase inspired by nature became a shortcut for everything from adaptive camouflage to biodegradable plastics. Stanford’s octopus-inspired synthetic skin mimics color-shifting complexity. Bioprinted microneedles borrow from bee stinger architecture. These breakthroughs represent genuine ecological wisdom translated into positive transformation. But walk down any product aisle and you’ll see the same phrase slapped on bottles with a leaf logo and nothing else.

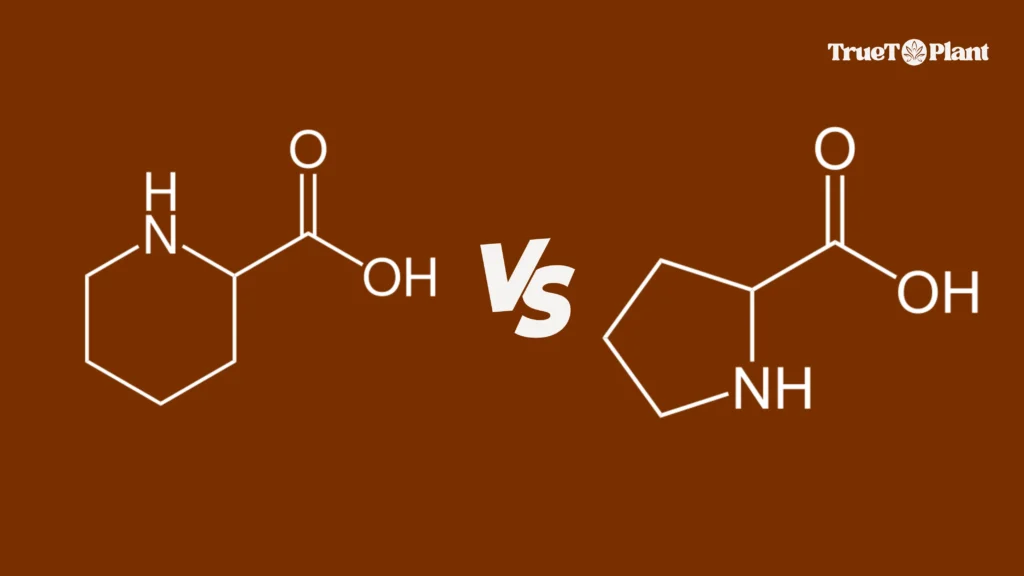

The tension sits here: nature operates through precise chemical languages. Plants don’t approximate – they express exact ratios of secondary metabolites that shift with soil, season, and stress. A chemotype isn’t a vibe. It’s a documented pattern of compounds like quinolizidine alkaloids or β-caryophyllene that define how a plant actually behaves. Yet most nature-inspired formulations skip this specificity entirely, choosing aesthetic over adaptation.

True To Plant approaches this differently. Studying chemotypic expression means mapping the molecular fingerprints plants use to survive changes and communicate through their environments. When you mirror those patterns instead of guessing, spending time outside becomes spending time inside botanical precision. That’s when green transition stops being marketing and starts being measurable.

What Does It Mean to Be Inspired by Nature?

The phrase inspired by nature stretches across wildly different territory. You’ll find it describing nature photography that captures morning light through leaves, and also labeling synthetic materials that mimic termite mound ventilation systems. Both claim the same inspiration, but they operate on fundamentally different levels of engagement.

Surface-level interpretation stops at visual resemblance – earthy tones, organic textures, a calming atmosphere that evokes spending time outside. Deeper work enters what researchers call ecological imagination, where observation of natural systems reveals principles you can translate into human contexts. This shift moves from copying what nature looks like to understanding how it actually functions.

Genuine nature inspiration requires systems thinking. Ecosystems don’t just arrange themselves beautifully – they self-organize through feedback loops, diversity, and circularity. When you apply ecological wisdom to formulation or design, you’re not approximating a forest’s vibe. You’re studying how specific plant secondary metabolites interact within living networks, then replicating those relationships with precision.

The green transition depends on this distinction. Climate change adaptation demands more than aesthetic gestures. Positive transformation happens when you treat natural patterns as documented chemical languages rather than decorative inspiration. Plants express exact molecular ratios for survival. Formulations claiming nature inspiration should mirror that specificity, not just borrow the marketing appeal of environmentally friendly language without the substance underneath.

How Does Nature Inspire Us? The Science Behind the Connection

Your brain doesn’t passively receive sensory input when you’re spending time outside. Research shows it actively predicts and regulates your internal state through allostasis, processing environmental signals to maintain physiological balance. Natural settings provide distinct sensory patterns – rustling leaves, shifting light, organic textures under your feet – that your neural systems interpret differently than synthetic environments. This isn’t abstract wellness theory. Studies tracking 1 million Danish children found that low childhood exposure to green spaces increased psychiatric disorder risk by 15-55%, revealing a dose-dependent relationship between nature contact and mental health outcomes.

The mechanism runs deeper than visual appeal. Alpha brain oscillations help you distinguish self from environment by integrating sight and touch, essentially creating boundaries between your body and the world around it. Natural landscapes offer sensory complexity that supports this integration process. When you practice nature photography, you’re not just capturing images – you’re engaging multiple sensory channels simultaneously, training attention on ecological patterns that your predictive brain uses to regulate internal states.

This science reframes what climate storytelling and adaptation actually mean for human wellbeing. Access to green space isn’t decorative. A 2024 review found that 70% of studies confirmed neighborhood vegetation protects mental health in disadvantaged populations, reducing depression and improving measurable outcomes. The green transition becomes personal when you recognize that ecological wisdom supports your nervous system’s fundamental operations, not just your aesthetic preferences.

What Is the Word for Something Inspired by Nature? Beyond Biomimicry

Design inspired by nature carries different names depending on how deeply you engage with the source material. Biomimicry describes functional imitation – studying how lotus leaves repel water through micro-nano surface structures, then engineering self-cleaning textiles that degrade 95% of organic stains within 20 minutes of sunlight. Biophilic design brings natural elements into built environments, prioritizing organic textures and calming atmospheres that support wellbeing. Nature-based solutions apply ecological processes to challenges like climate change adaptation, from wetland restoration for flood management to plant chemistry variation that informs resilient crop development.

The terminology evolved alongside our understanding. Early uses of “nature-inspired” leaned aesthetic – nature photography translated into visual motifs. Modern applications demand precision. Indigenous agricultural practices demonstrate this depth, emulating not just plant morphologies but entire ecological relationships for sustainable land stewardship. That’s adaptation as documented practice, not decorative reference.

| Term | Focus | Application Example |

| Biomimicry | Functional replication of biological strategies | Lotus-effect coatings with 150° contact angles |

| Biophilic Design | Integrating natural elements into human spaces | Living walls, natural materials in interiors |

| Nature-Based Solutions | Ecological processes addressing societal challenges | Wetland restoration, climate-resilient agriculture |

Greenwashing thrives in this gap between terminology and substance. A product labeled “inspired by nature” might reference nothing beyond earthy tones and a leaf graphic. Genuine nature inspiration requires measurable criteria – documented ecological wisdom, traceable natural materials, or verified positive transformation metrics. Spending time outside observing how ecosystems self-organize through diversity and feedback loops teaches more than any marketing claim. The green transition depends on treating natural patterns as precise chemical languages, not vague aesthetic inspiration.

5 Ways Nature Inspires Design, Chemistry, and Innovation

- High-Speed Rail Aerodynamics – When engineer Eiji Nakatsu redesigned Japan’s Shinkansen 500 Series, he studied kingfisher beaks to solve sonic boom problems in tunnels. The bird’s streamlined structure inspired a nose shape that reduced noise by 10% and cut air resistance by 4.3%, enabling speeds up to 300 km/h with lower power consumption. This wasn’t about copying nature’s appearance – it required reading nature’s functional geometry and translating aerodynamic principles into engineering specifications.

- Space-Ready Materials – NASA researchers developed nacre-inspired nanocomposite films for low Earth orbit applications by studying how mollusk shells layer minerals for strength. These Polyimide-Mica materials resist atomic oxygen degradation while maintaining thermal stability in extreme conditions. Separately, DNA-inspired nanomaterials use controlled self-assembly processes observed in biological systems to create drug delivery platforms with enhanced biocompatibility. Both examples show how plant chemistry diversity and broader biomimetic manufacturing turn natural assembly strategies into practical solutions for environments where traditional materials fail.

- Drug Discovery Through Biomimetic Synthesis – Chemists synthesized anti-inflammatory compounds from Ganoderma mushrooms using biomimetic convergent strategies that mirror how plants as natural chemists build complex molecules. The process employs hetero-Diels-Alder and aldol cascade reactions that replicate natural product formation pathways. This approach doesn’t just extract existing compounds – it decodes nature’s chemical logic to manufacture therapeutic molecules more efficiently.

- Self-Cleaning Surfaces – Lotus leaf microstructures inspired textiles that degrade 95% of organic stains within 20 minutes of sunlight exposure. The innovation lies in accurately replicating nano surface architectures that create 150° contact angles, causing water to bead and roll away with contaminants. Janine Benyus, who pioneered biomimicry research, emphasizes this functional depth – studying how organisms solve problems through billions of years of adaptation.

- Indigenous Agricultural Systems – Traditional farming practices demonstrate long-term adaptation by emulating entire ecological relationships rather than isolated traits. These systems integrate crop diversity, soil management, and water cycles based on observing how natural ecosystems maintain productivity across generations without external inputs, offering climate change adaptation strategies grounded in documented ecological wisdom.

How to Be Inspired by Nature: From Observation to Application

Step 1: Document Specific Systems, Not Vague Aesthetics

Spending time outside shifts from passive recreation to active research when you document what you observe with precision. Choose one system – how water moves across leaf surfaces, how soil aggregates form around roots, how seasonal stress changes plant aroma. Record measurable details instead of general impressions. Nature photography trains your eye to notice light angles and textures, but genuine inspiration requires going further: sketch structural relationships, note timing patterns, measure physical dimensions when possible.

Step 2: Identify the Functional Problem Being Solved

Every natural pattern exists because it solves a survival challenge. Waxy leaf coatings aren’t decorative – they prevent water loss during drought. Root exudates aren’t random – they recruit beneficial microbes and chelate nutrients. Ask what environmental pressure shaped the adaptation you’re observing. Climate change intensifies these pressures, making ecological wisdom more valuable. When you understand the problem a plant solves through its chemistry or structure, you can translate that strategy into human applications rather than just copying surface appearances.

Step 3: Map the Chemical or Structural Logic

Surface-level biomimicry stops at visual resemblance. Deeper work decodes the molecular or architectural principles that make natural systems function. True To Plant demonstrates this through chemotype essential oil analysis – mapping exact ratios of terpenes and secondary metabolites that define how plants actually behave under specific conditions. You can apply similar rigor to any natural system by identifying the core mechanism, whether it’s hierarchical material layering, feedback-driven regulation, or chemical signaling networks.

Step 4: Test Against Measurable Standards

Green transition claims need verification beyond marketing language. Apply concrete criteria: Does your nature-inspired solution replicate documented ecological processes? Can you trace ingredients to specific botanical sources? Do performance metrics match or exceed the natural system’s efficiency? Projects like Seattle’s Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel succeed because they measure stormwater filtration rates and native plant establishment, turning ecological principles into quantifiable positive transformation rather than aesthetic gestures.

Real vs. Superficial: When ‘Nature-Inspired’ Is Just Greenwashing

SC Johnson marketed Windex bottles as “100% ocean plastic” when the material came from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Haiti – ocean-bound waste that never touched marine environments. IKEA sold FSC-certified beechwood chairs containing illegally harvested timber from Ukraine’s Carpathian forests. Both examples reveal how verification systems fail when nature-inspired claims lack traceable standards. Greenwashing enforcement surged accordingly – flagged firms rose 19% globally in 2025, reaching 294 companies, while banking sector violations jumped 70% in 2023 alone.

The pattern repeats across home decor inspired by nature. Mass-produced items carry leaf graphics and earthy tones without substance underneath. Marketing promises “thoughtfully crafted” quality, but products lack the documented ecological wisdom that defines genuine adaptation. Climate change demands precision, not aesthetic gestures. The green transition requires measurable criteria.

The IUCN Global Standard offers one framework – 8 criteria and 28 indicators evaluating whether nature-based solutions address societal challenges through verified ecological processes. LEED certification establishes benchmarks for sustainable building materials and energy efficiency. These systems work when applied rigorously, measuring positive transformation instead of accepting vague environmental claims.

True To Plant demonstrates this accountability through chemotypic mapping. Formulations mirror exact secondary metabolite ratios plants express under documented conditions – specific terpene profiles, traceable botanical sources, honest communication about every ingredient. That’s climate storytelling backed by molecular fingerprints, not marketing language borrowing credibility from spending time outside. When nature inspiration becomes measurable, greenwashing loses ground to genuine ecological understanding.

Nature as Blueprint, Not Just Backdrop

When formulation claims inspiration from nature, the distinction between blueprint and backdrop determines everything. Biomimicry replicates documented natural processes with precision, while bioinspiration adapts key principles into new contexts. Both approaches demand more than aesthetic reference – they require decoding the chemical logic plants use to survive. Unregulated terms like “natural” and “organic” let brands slap leaf graphics on products without traceability, turning ecological wisdom into empty marketing.

True To Plant treats this differently. Chemotype mapping documents exact terpene ratios – β-caryophyllene percentages, phenolic profiles, metabolite patterns plants express under specific conditions. That’s treating botanical systems as blueprints, not decorative inspiration. The green transition depends on this rigor: verifiable standards, traceable ingredients, honest communication about what actually goes into formulations. Nature operates through precise chemical languages. Genuine nature inspiration mirrors that specificity instead of approximating it.