The Hidden Language of Secondary Metabolites

1. Secondary Metabolites vs Primary Metabolites: What’s the Difference?

Plants are far more than passive green beings. Behind their serene leaves and blooms lies a bustling chemical industry, producing hundreds of thousands of compounds that serve purposes beyond growth or reproduction. These are the secondary metabolites, the language of nature, which we call chemistry. In this article we’ll explore what these compounds are, how plants produce them, why they do it, and how the environment shapes the chemical profile of a plant.

Every plant cell runs a metabolic engine. Some of the products of that engine are essential: carbohydrates to fuel the plant, amino acids for proteins, lipids for membranes, nucleic acids for genetic material. These are primary metabolites, the compounds required for growth, development, and reproduction.

In contrast, secondary metabolites (also called specialised metabolites) are compounds that are not directly required for those basic life processes. Instead they often mediate interactions between the plant and its environment for example, chemical defense, signalling to pollinators, microbial interactions.

“Secondary metabolites are metabolic intermediates or products which are not essential to growth and life of the producing plants but rather required for interaction of plants with their environment.”

Why the distinction matters

The distinction matters because:

- Primary metabolite levels tend to be relatively stable and conserved across species (e.g., glucose, amino acids).

- Secondary metabolites vary widely by species, environment, stress, evolutionary history.

- From an applied perspective (agriculture, pharmacology, ecology) secondary metabolites represent the “interesting” chemistry: colors, aromas, toxins, signalling molecules.

A quick table:

2. How Light, Soil, and Stress Shape a Plant’s Chemical Expression

Plants do not live in a vacuum. Their chemical output (the secondary metabolites) is deeply influenced by environmental, edaphic (soil), biological, and abiotic stress factors.

Light and UV

High levels of UV radiation can damage plant cells. In response, plants ramp up production of phenolic compounds (a class of secondary metabolites) which absorb UV and protect tissues. For example flavonoids act as UV-filters.

Soil nutrients and water stress

When nutrients are limited or water is scarce, plants often shift metabolic resources. Some secondary metabolite pathways may be up-regulated as defense mechanisms or to alter root exudation (chemicals secreted into soil) which affect microbial communities or competing plants (allelopathy). For instance, certain phenolics or flavonoids in the roots may suppress neighboring plants’ growth.

Biological stress: herbivory, pathogens

When a plant is attacked by herbivores or pathogens, it often activates chemical defenses: production of alkaloids or terpenoids that repel insects or inhibit microbes. For example, certain alkaloids act as toxins to herbivores.

Why this matters for chemical “expression”

The environmental context means two plants of the same species can have quite different chemical profiles. Soil composition, light exposure, altitude, temperature, and stress all contribute. This dynamic nature makes plant secondary metabolite profiles rich but also harder to predict.

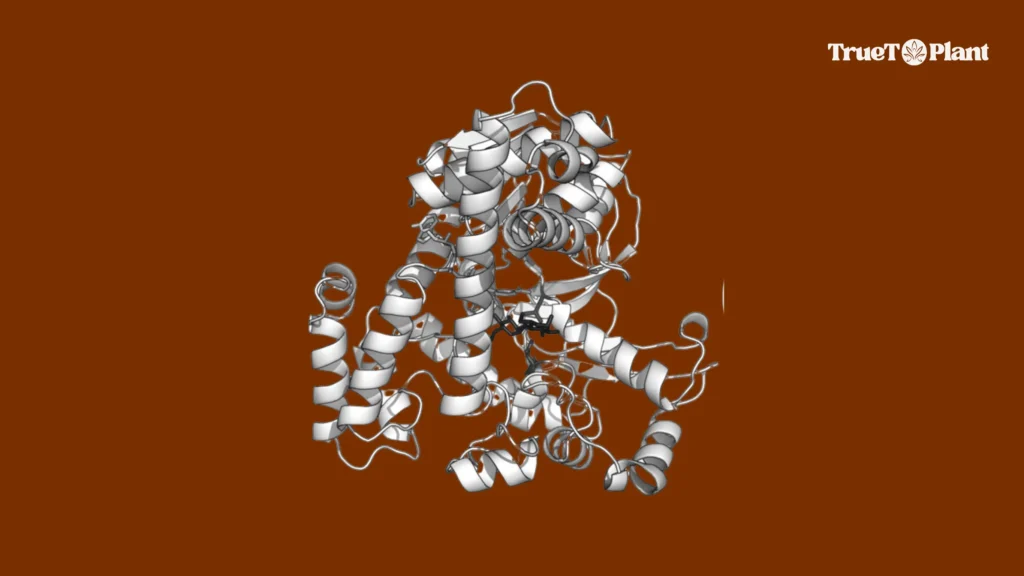

3. The Role of Enzymes in Plant Metabolite Formation

At the heart of producing secondary metabolites lies enzyme-controlled biosynthetic pathways. These pathways link primary metabolism into the specialized routes that build secondary compounds.

How the biosynthetic pathways work

- Building blocks from primary metabolism (e.g., amino acids, sugars, acetyl CoA, etc.) feed into enzyme cascades that lead to complex molecules.

- For example, flavonoids derive from the amino acid phenylalanine via the phenylpropanoid pathway: phenylalanine → cinnamic acid (via phenylalanine ammonia-lyase) → various downstream enzymes → flavonoid skeletons.

- Terpenoids arise from isoprene units (C₅H₈) repeatedly linked, catalyzed by terpene synthases and modifications (oxidation, glycosylation, etc.).

Why enzyme regulation is key

- Enzyme expression is often induced by stress signals (wounding, UV, herbivory).

- Enzyme localisation matters: some reactions happen in roots, others in leaves, or specialised organs. For example, the alkaloid atropine is primarily synthesized in the root of Atropa belladonna.

- Because these pathways are modular and complex, slight variations (enzyme isoforms, gene regulation) lead to big chemical diversity between plant species.

A simple analogy

Imagine a factory (the plant cell) with a main production line (primary metabolism). At various stations, side-arms branch off to build specialty products (secondary metabolites). The “side-arms” are enzyme systems, triggered only when the “order” (stress, environment, signalling) comes in.

4. How Evolution Turned Plants into Natural Chemists

Nature is the ultimate chemist. Over millions of years, plants evolved not just to photosynthesize, but to survive, compete, and thrive and from that position chemistry became one of their primary tools.

Evolutionary drivers

- Plants are sessile, they cannot flee herbivores or pathogens. They instead rely on chemical defences, deterrents, toxins, or mutualistic attractants (for pollinators, microbes).

- Chemical diversity allows niche specialization: different plants evolving different metabolite sets to exploit or defend against particular challenges. Studies show that metabolite distributions across species follow heterogenous (power-law) patterns, indicating evolutionary diversification.

- Some compounds originally evolved for one purpose (defense) were later co-opted (exapted) for signalling, attraction, or even structural roles.

Co-evolution and arms-races

Herbivores and pathogens evolve to resist or exploit plant chemicals. In turn, plants may evolve new chemical variants. Over time this arms-race drives complexity. For example, some insects sequester plant toxins to become toxic themselves.

Why chemical creativity matters

Plants that diversify their chemistry may gain competitive advantage: attract pollinators, repel pests, survive abiotic stress. This gives selective pressure for maintaining and diversifying secondary metabolite pathways.

5. Why Plants Produce Terpenes, Alkaloids, and Flavonoids, Beyond Aroma and Color

When one hears “plant chemistry”, often the first things that come to mind are aromas (terpenes) or colors (flavonoids). But the function of these compounds is far broader.

Terpenes / terpenoids

- Terpenoids are the largest class of plant secondary metabolites, about 60% of known natural products are terpenoid in origin.

- Roles: volatile terpenes may attract pollinators or beneficial insects; others deter herbivores or pathogens; some act as hormones (though many hormones are now considered primary or semi-primary).

- Example: Artemisinin (from Artemisia annua) is a sesquiterpene lactone used medically.

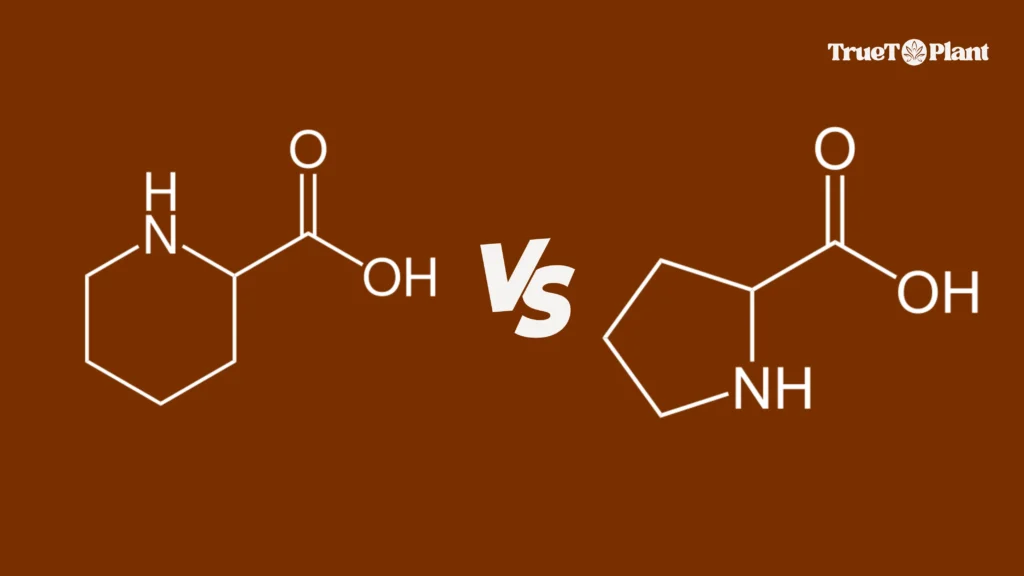

Alkaloids

- Alkaloids contain nitrogen and are often biologically active (toxic, neurological-acting).

- They are often part of a plant’s defense system by interfering with animal physiology.

- Example: Nicotine from tobacco plants, or Atropine from Atropa belladonna.

Flavonoids and phenolics

- These arise from the phenylpropanoid pathway and include flavonoids, tannins, lignans, phenolic acids.

- They serve as UV-protectants, structural components (lignin), antioxidants, signalling molecules, pigmentation (flowers, fruits) which in turn attracts pollinators.

- Example: Catechin, a flavonoid found across plants, is involved in defense and allelopathy.

Soil and root-related compounds

- Some plants produce glucosinolates or cyanogenic glycosides which release toxic compounds upon damage (e.g., cyanide).

- These compounds protect seeds, roots, or entire plants from herbivory or microbial attack.

Beyond “smell & color”

While aroma and color are visible or perceptible outputs, the real ecological work is behind the scenes: chemical defense, plant-plant interaction, root exudation, signalling in the rhizosphere, microbial symbiosis, abiotic stress mitigation.

6. How to Read a Plant’s Chemical Profile Like a Map

If you treat a plant like a chemical factory, then its “chemical profile” is akin to the inventory of products on its shelves. Understanding this profile helps in ecology, phytochemistry, agriculture, medicine.

What to look for

- Major classes present: Are terpenes dominant? Flavonoids? Alkaloids?

- Tissue specificity: Leaves vs roots vs flowers vs seeds often differ in metabolite composition.

- Environmental context: Growing altitude, light exposure, soil type, local stressors influence profile.

- Quantitative versus qualitative: The levels of a given compound matter; minor compounds may have major ecological roles.

- Biosynthetic signatures: E.g., presence of flavonoids indicates active phenylpropanoid pathway; many terpenoids imply strong isoprenoid pathway involvement.

- Functional inference: If you see many alkaloids, defense against herbivores may be the priority; many volatiles may signal pollination strategy.

Practical steps for analysis

- Use metabolomics (sophisticated analytics) to identify compounds and their levels.

- Relate findings to plant provenance: altitude, soil composition, climate history.

- Consider stress history: e.g., drought, pathogen exposure, nutrient limitation.

- Map out biosynthetic routes to infer which enzymes and precursors are active.

- Interpret ecological meaning: what defensive, signalling or symbiotic role might this profile indicate.

When you link this back to “plant chemistry”, you start seeing each plant as not just a living organism but as a unique chemical signature shaped by genes and environment.

7. The Science Behind “Full-Spectrum” Plant Extracts

In fields such as herbal medicine, nutraceuticals, or botanical extracts the term “full-spectrum” is used to suggest the presence of a broad array of secondary metabolites rather than isolation of a single compound.

Why full-spectrum matters

- It mirrors how the plant functions in nature: multiple compounds working together (synergy, co-metabolism).

- Some minor compounds modulate the activity or bioavailability of major compounds.

- It preserves the chemical “fingerprint” of the plant, which may correlate with traditional use.

Scientific caveats

- Because plants vary by environment (light, soil, stress) the chemical profile of one batch may differ from another.

- The presence of many metabolites complicates standardisation and dosing.

- “Full-spectrum” is a marketing term unless backed by thorough analysis of metabolite composition and quantitative levels.

How chemistry supports the concept

Since secondary metabolites derive from multiple pathways (phenylpropanoid, isoprenoid, alkaloid, etc), a full-spectrum extract implicitly taps into multiple biosynthetic routes. An extract rich in flavonoids + terpenes + alkaloids suggests a plant under diverse ecological pressures, which may in turn reflect robustness of effect.

8. How Temperature and Altitude Change the Chemistry of Botanicals

Altitude, temperature fluctuations, and extreme environments push plants into metabolic stress and stress often triggers secondary metabolite production.

Altitude

- Higher altitudes often mean higher UV levels, cooler temperatures, shorter growing seasons. These stressors stimulate production of UV-protective flavonoids, or anti-herbivory terpenoids.

- Example: members of the genus Oryza (rice) show significant specialized metabolite diversity across different altitudes and ecological zones.

Temperature & seasonality

- Cold stress or frost risk lead plants to produce antifreeze proteins and secondary metabolites that stabilize membranes or scavenge free radicals.

- Heat stress likewise may trigger volatile emission (terpenes) that protect or signal.

- Variable temperature often correlates with higher chemical diversity.

Why altitudes and climates matter for plant chemistry

In essence, the more “challenging” the environment, the more incentive for the plant to deploy chemical defenses or adaptations. This gives botanical extracts from unusual climates (high altitude, harsh soils, cold zones) special interest for their richer chemical profiles.

9. How Climate Change Threatens Plant Chemical Diversity

If plant secondary metabolites are tied to the environment, then climate change poses a direct threat to their diversity and function.

Mechanisms of threat

- Changes in temperature, rainfall, and CO₂ levels alter plant stress responses, meaning the cues for secondary metabolite production shift or disappear.

- Altered herbivore/pollinator dynamics may reduce selective pressure for certain chemical traits.

- Habitat loss and species extinction mean loss of unique metabolic pathways and compounds.

Why it matters

- Loss of chemical diversity in plants means fewer opportunities for discovery of novel compounds (for medicine, agriculture).

- Ecosystem resilience may decline if plants lose the chemical “tools” to adapt to new stresses.

- For industries relying on botanicals (phytomedicine, nutraceuticals, flavors), reduced chemical variation and shifting profiles may undermine consistency and efficacy.

Researchers increasingly focus on preserving plant biodiversity and the environments that drive chemical diversity. Understanding how the environment shapes plant chemistry helps forecast the impacts of a warming world and underscores the value of sustainable harvesting, conservation, and habitat protection.

10. Bringing It All Together

The chemistry of plants is not an after-thought. It is central to how plants survive, thrive, and interact with their world. From enzymes quietly assembling complex molecules, to an altitude-stressed shrub producing a suite of flavonoids for UV defence, to a herbivore-resistant alkaloid in seeds, the story of secondary metabolites is a narrative of adaptation, survival, signalling, and interaction.

If you approach a plant through the lens of “plant chemistry”, you can read its environment, history, stressors and evolutionary past. The profile of secondary metabolites is a map, one that reflects genes, enzymes, environment, and ecology.

For anyone interested in botanical extracts, ecological chemistry, agriculture or pharmacology, recognising the interplay of environment and chemical production opens doors to applications (and caution) far beyond aroma and colour. In short: plants make chemistry not by accident but by design. Further demonstration of these concepts can be found in the wonderful documentary by PBS called What Plant Talk About.