You’ve probably noticed that lavender from one garden can have a completely different scent than lavender from another. This isn’t your imagination it’s plant chemistry at work. The aromatic profile of any plant that smells good comes from volatile compounds, tiny molecules that float through the air to your nose.

Here’s where it gets interesting: the same species can produce entirely different combinations of these scent compounds. A rose might produce high levels of citronellol in one garden but favor geraniol in another, creating distinct floral notes despite identical DNA. Scientists call these variations chemotypes, a concept explored in detail in this guide to essential oil chemotypes.

Think of chemotypes as recipes written in the same cookbook but using different ingredient ratios. Two basil plants might both contain linalool and eugenol, but one emphasizes the sweet, floral linalool while the other leans into eugenol’s spicy character. This botanical diversity explains why flowers you plant that smell good can surprise you with unexpected scent varieties, even when you’re growing the exact same species your neighbor cultivates.

What Is One Reason That Some Plants Have a Strong Scent?

Strong fragrance serves as a plant’s survival strategy, not just a pleasant bonus for your garden. When you encounter an intensely fragrant jasmine or powerfully aromatic lavender, you’re experiencing the plant’s sophisticated defense and reproduction system in action.

Plants manufacture volatile organic compounds (VOCs) through complex biochemical pathways involved in plant metabolite formation. These molecules are light enough to travel through air for two critical purposes. First, they act as bodyguards, deterring hungry insects and attracting predators that feed on plant-eating pests. Second, they function as botanical billboards, broadcasting “pollinator wanted” signals across your garden.

The intensity of a plant’s scent directly correlates to its metabolite concentration. Plants producing higher volumes of these volatile compounds create stronger aromas that travel farther distances. Roses releasing abundant citronellol molecules generate more powerful fragrances than those producing minimal amounts much like turning up the volume on nature’s broadcast system.

This concentration varies based on environmental pressures and genetic programming. A plant facing frequent pest attacks might ramp up its VOC production, creating notably stronger scents than its unstressed neighbors.

Understanding this relationship between compound concentration and scent strength helps explain why some fragrant plant guides emphasize growing conditions. When you cultivate plants that smell good, you’re essentially managing their metabolite production the foundation of every natural fragrance you enjoy.

Why Do Plants Have Different Smells?

The fragrance variations you notice in your garden trace back to chemotypes genetic expressions that determine which chemical compounds dominate a plant’s aromatic profile. Even plants sharing identical DNA can smell completely different based on their unique metabolite combinations, particularly variations in plant secondary metabolites.

Consider rosemary growing across different regions. One plant might produce camphor-dominant oil with sharp, medicinal notes, while another from the same species creates verbenone-rich oil with softer, herbaceous character. Both remain true rosemary plants, yet their scent profiles diverge dramatically.

Spearmint and peppermint demonstrate this principle clearly. Though closely related, spearmint concentrates carvone in its essential oils, creating a sweet, gentle fragrance. Peppermint emphasizes menthol production instead, delivering a cooling, intense aroma.

Climate plays a particularly powerful role in chemotype expression. A thyme plant experiencing Mediterranean heat might amplify thymol production, while the same variety in cooler climates could favor linalool instead.

This botanical flexibility explains why gardeners sometimes struggle to replicate specific scents. You’re not just growing a species—you’re cultivating a particular chemical expression shaped by your environment.

Understanding Chemotypes: The Chemical Identity Within Species

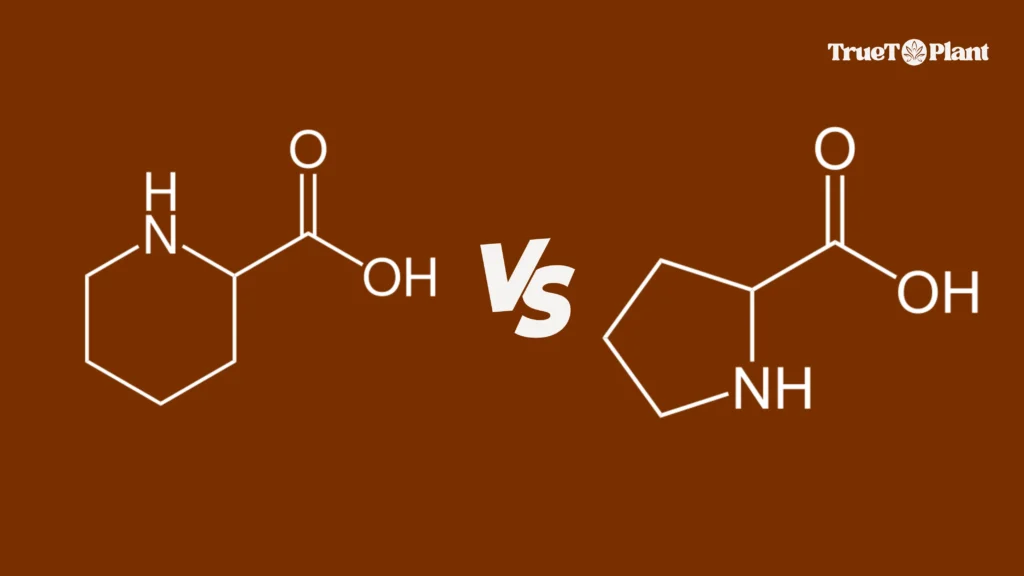

Chemotype defines a botanical identity crisis in the best possible way. This scientific term describes plants from the same species that produce fundamentally different chemical compositions despite sharing genetic blueprints.

Environmental conditions act as master switches for these chemical expressions. Soil mineral content triggers specific biosynthetic pathways, directing which fragrance compounds a plant prioritizes. Altitude influences terpenoid production the molecular family responsible for most plant aromas and widely studied in terpene science, including resources like Cannabis Terpenes.

Climate variables compound these effects. Drought stress often increases essential oil concentration but alters which compounds predominate. Mediterranean oregano experiencing dry summers typically produces carvacrol-rich oils, while plants receiving consistent moisture lean toward softer, thymol forward profiles.

Genetic variation adds another layer of complexity. While chemotypes within a species share core DNA, subtle genetic differences determine metabolic flexibility how readily plants adjust their chemical output when environmental signals change.

Which Type of Plant Emits the Most Fragrance?

Certain botanical families consistently outperform others in fragrance production, with Lamiaceae (mint family) and Rosaceae (rose family) leading the aromatic rankings. These plants produce exceptionally high concentrations of volatile compounds.

What makes these families particularly interesting is how chemotype variations create dramatically different intensities within the same species. Rosemary alone expresses multiple chemotypes, each with distinct aromatic strength depending on dominant compounds like camphor or 1,8-cineole.

Rosaceae family members, including roses, produce β-damascenone a potent aromatic compound responsible for intense floral diffusion. This explains why small rose plantings can perfume entire gardens.

Understanding chemotype variation helps predict fragrance strength more accurately than plant labels alone.

Why Do Plants Have Bright, Sweet-Smelling Flowers?

Bright petals and sweet fragrances work as coordinated advertising campaigns designed to attract specific pollinator species. Plants evolve precise combinations of visual and scent cues that match pollinator preferences.

Chemotype variations directly influence which pollinators a plant attracts. Ester-rich chemotypes produce fruity aromas, while monoterpene-heavy profiles broadcast sharp floral signals.

Gardens containing diverse chemotypes attract a wider range of pollinators because each plant emits a unique chemical message tailored to different species.

Real-World Chemotype Examples: From Basil to Cannabis

Chemotypes influence everyday choices from cooking herbs to wellness products. Basil demonstrates this clearly, with linalool-dominant chemotypes offering sweet aroma and eugenol rich types delivering clove-like spice.

Thyme shows even broader variation, with thymol, linalool, and geraniol chemotypes serving different culinary and aromatic purposes.

Cannabis offers the most widely recognized chemotype framework, dividing plants by cannabinoid ratios and terpene dominance. Terpene profiles such as myrcene or limonene dominance shape aroma and effects, a subject explored extensively across terpene-focused platforms like Cannabis Terpenes.

Choosing Fragrant Plants by Chemotype for Your Garden

Finding chemotype information requires intentional sourcing. Specialty growers sometimes provide essential oil analyses or GC-MS summaries identifying dominant compounds.

Your climate determines which chemotypes thrive. Hot, dry regions favor camphor-rich plants, while cooler climates preserve delicate linalool profiles.

Match chemotypes to purpose culinary, pollinator attraction, or fragrance intensity rather than relying on species names alone.

The Future of Fragrance: Respecting Plant Complexity

Understanding chemotypes changes how we interact with fragrant plants. Rather than generic labels, chemotype awareness delivers precision, authenticity, and predictable results.

Brands rooted in chemical transparency such as Entour and True To Plant reflect this shift toward respecting complete plant chemistry instead of isolating single compounds.

When selecting flowers to plant that smell good, ask deeper questions. Which chemotype thrives in your microclimate? What compound ratios define your ideal scent?

This approach transforms gardening and botanical product selection into informed chemical curation ensuring every plant delivers the fragrance complexity you’re actually seeking.